Excerpts from the Global Nonviolence Action Database

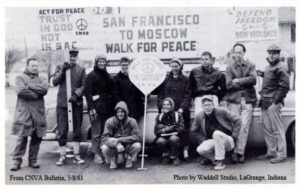

On December 1, 1960, just after a rally in San Francisco, ten members of the Committee for Non-Violent Action marched out of the city, intent on marching across the country, all the way to Moscow in the Soviet Union. Their chances for success were slim.

Their goals were simple. The CNVA called on the governments of the world (particularly those that they marched though) to disarm, train citizens in nonviolent resistance, and settle international disputes through negotiation and compromise. They urged citizens of all countries to refuse to serve in their militaries, or to have anything to do with military industry. Marchers were only allowed to join in the march if they were committed to unilateral disarmament and nonviolent civil disobedience if the situation called for it.

For the next six months, these activists marched across the United States. Though their number rarely rose above forty, the march tended to attract the local media as they walked through cities. The reception was mixed and many times they were threatened with violence. In each city, the marchers handed out CNVA leaflets advocating disarmament.

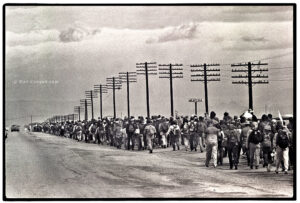

They arrived in Washington DC on May 13, held a vigil at the Pentagon, and met with presidential aide Arthur Schlesinger. Hundreds of people joined the march as they walked through New York on May 28 and demonstrated at the United Nations building. After nearly 4,000 miles, the CNVA selected its 15 best, most committed activists and put them on a plane to London.

Britain welcomed the protesters with enthusiasm. 6,000 people welcomed them into Trafalgar Square and marchers from Britain and nearby Scandinavian countries added an international flavor to the campaign.

As the marchers closed in on the Iron Curtain line, observers and supporters began to speculate in earnest about their chances of entering Communist territory. Many anti-war activists feared that if the marchers were turned back, the Cold War would only intensify in the West – refusal to allow the marchers might be interpreted by the US as a signal the Russia was committed to significant additional militarization. However, the march continued, as Muste and others recognized that the only thing holding the group together was the common drive towards Moscow. Any hesitation would lead to disillusionment and despair among the marchers and all their accumulated momentum would be lost. Muste and others wrote directly to Soviet Premier Khrushchev emphasizing the nonviolent nature of the march and requesting permission to enter Communist territory.

The march entered West Germany in July. Though the police there were friendly and supportive of the march, they were under orders to stop any overt political activities. Thus leafleting was prohibited and police occasionally arrested marchers as they demonstrated in front of German government buildings.

As the marchers crossed Western Europe, progress had been made with Khrushchev. The march crossed into East Germany on August 7, 1961. However, they were not allowed free reign to leaflet and demonstrate. They were placed under constant surveillance and all media coverage ignored every part of their campaign that did not agree with Soviet policy. Though they were not allowed anywhere near East Berlin (and indeed had a tense encounter with an East German official when they demanded to be allowed into the city), they were able to distribute 15,000 leaflets, and were allowed to continue through Eastern Europe as long as they agreed not to engage in civil disobedience.

The march was welcomed in Poland and suffered no governmental resistance of any kind during their time in the country outside of occasional media censorship. The marchers entered Russia on September 15 and marched to Moscow in 18 days. While there, they met with the wife of Khrushchev and convinced her to relay a message about the dangers of nuclear testing to her husband.

The marchers distributed 100,000 leaflets in Russia, spoke at an incredible number of public events, and were the first group to engage in significant political agitation in the Soviet Union. One reporter described the march as “the most important expression of intellectual freedom [he] had seen in the Soviet Union.” The marchers returned home to America in mid-October after more than 6,000 miles of walking nearly halfway around the world. Though they did not manage to convince any government to de-militarize, their march educated millions of people about the dangers of nuclear testing.